|

|

| jbm > Volume 22(3); 2015 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

Methods

Results

Conclusions

References

Fig. 1

Factors showed the lowest calcium intake by region. *Calcium intake. †Calcium intakes ratio vs. the Korean recommended calcium allowance. NBLSS, national basic livelihood security supply; NDLS, national dietary life supply.

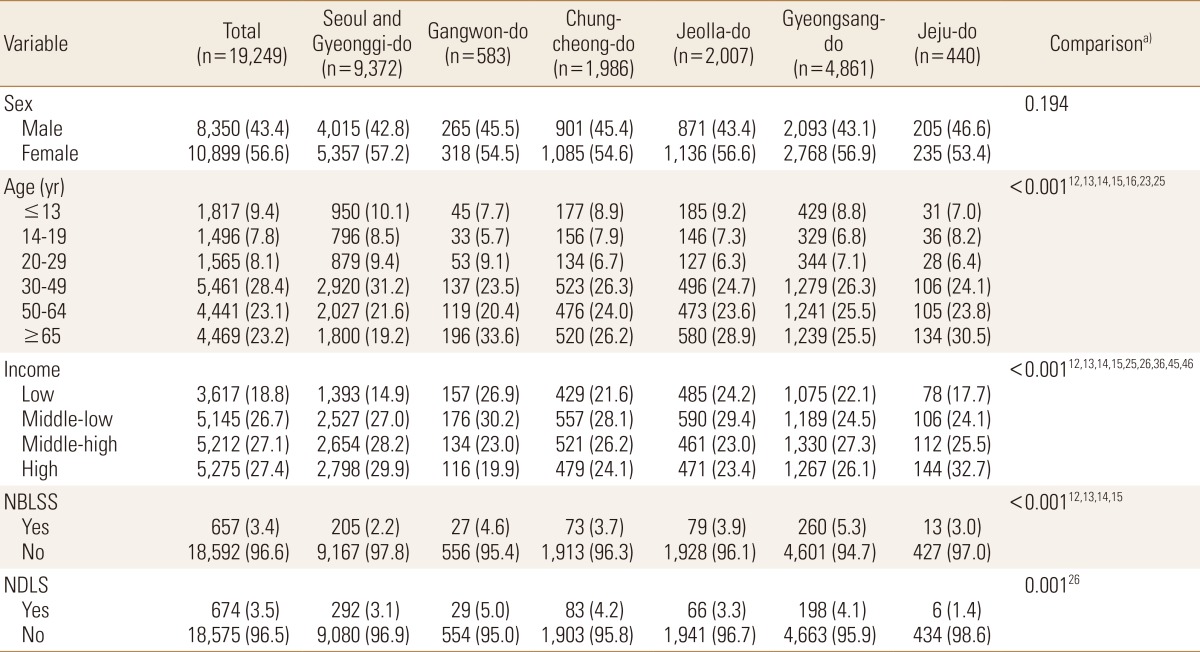

Table 1

Regional distribution

Data was presented as frequency and percentage.

a)Posthoc comparison was performed by Bonferroni's method, Posthoc comparison: ij means that the i-th group and j-th group had a significant difference (i, j=1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; group 1=Seoul and Gyeonggi-do, group 2=Gangwon-do, group 3=Chungcheong-do, group 4=Jeolla-do, group 5=Gyeongsang-do, group 6=Jeju-do).

NBLSS, national basic livelihood security supply; NDLS, national dietary life supply; yr, year.

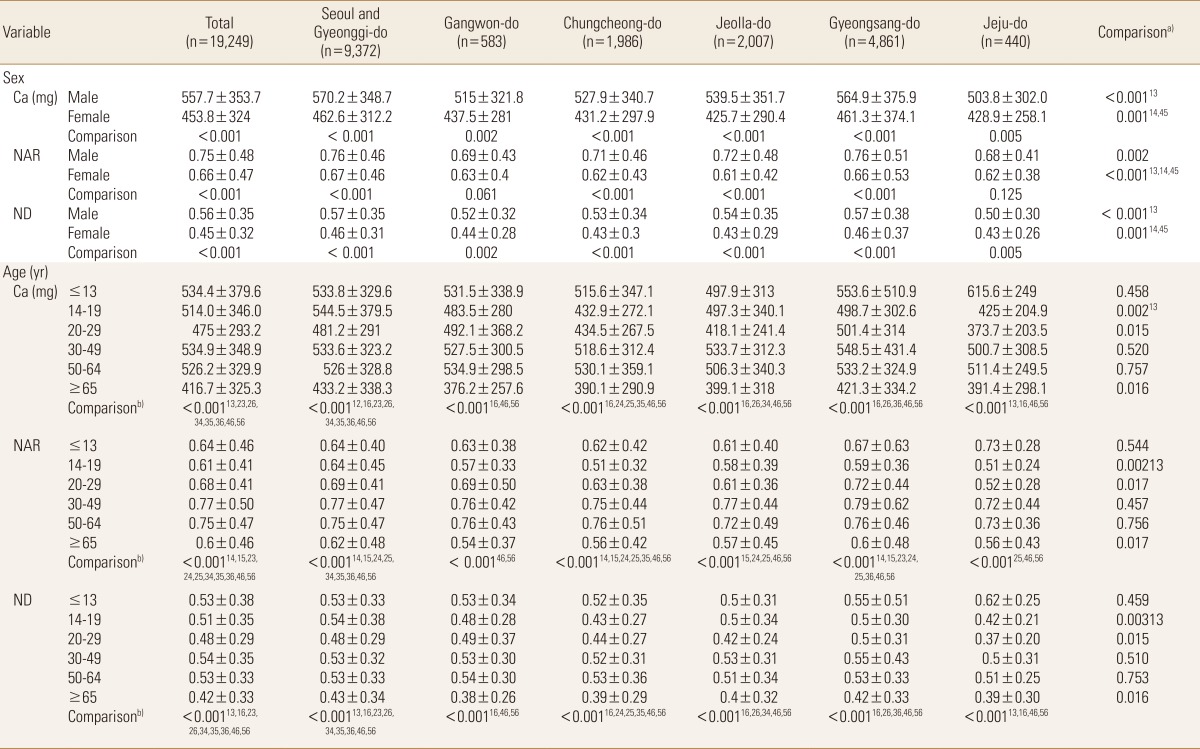

Table 2

Comparison of calcium intake status by the age and sex

Data was presented as mean and standard deviation.

a),b)Posthoc comparison was performed by Bonferroni's method.

a)Posthoc comparison: ij means that the i-th group and j-th group had a significant difference (i, j=1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; group 1=Seoul and Gyeonggi-do, group 2=Gangwon-do, group 3=Chungcheong-do, group 4=Jeolla-do, group 5=Gyeongsang-do, group 6=Jeju-do).

b)Posthoc comparison: ij means that the i-th group and j-th group had a significant difference (i, j=1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; group 1=age ≤13 yr, group 2=14-19 yr, group 3=20-29 yr; group 4=30-49 yr, group 5=50-64 yr, group 6=≥65 yr).

NAR, nutrient adequacy ratio; ND, nutrient density; yr, year.

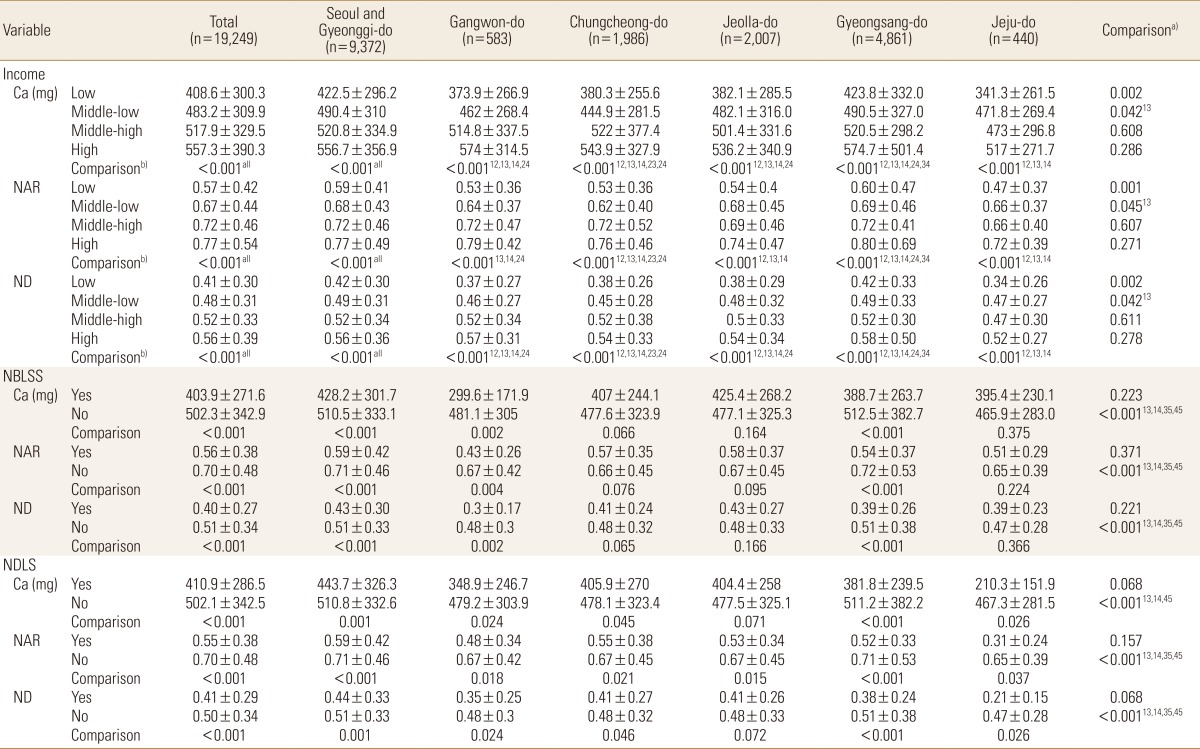

Table 3

Comparison of calcium intake status by the socioeconomic status

Data was presented as mean and standard deviation.

a),b)Posthoc comparison was performed by Bonferroni's method.

a)Posthoc comparison: ij means that the i-th group and j-th group had a significant difference (i, j=1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; group 1=Seoul and Gyeonggi-do, group 2=Gangwon-do, group 3=Chungcheong-do, group 4=Jeolla-do, group 5=Gyeongsang-do, group 6=Jeju-do).

b)Posthoc comparison: ij means that the i-th group and j-th group had a significant difference (i, j=1, 2, 3, 4; group 1=low income, group 2=middle-low, group 3=middle-high, group 4=high); all means that all pairs of groups had a significant difference.

NAR, nutrient adequacy ratio; ND, nutrient density; yr, year; NBLSS, national basic livelihood security supply; NDLS, national dietary life supply.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 8 Crossref

- 0

- 2,948 View

- 10 Download

- Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print