Impact of COVID-19 on the Incidence of Fragility Fracture in South Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the consequent social distancing period are thought to have influenced the incidence of osteoporotic fracture in various ways, but the exact changes have not yet been well elucidated. The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of osteoporotic fracture using a nationwide cohort.

Methods

The monthly incidence rates of vertebral; hip; and non-vertebral, non-hip fractures were collected from a nationwide database of the Korean National Health Insurance Review and Assessment from July 2016 to June 2021. Segmented regression models were used to assess the change in levels and trends in the monthly incidence of osteoporotic fractures.

Results

There was a step decrease in the incidence of vertebral fractures for both males (6.181 per 100,000, P=0.002) and females (19.299 per 100,000, P=0.006). However, there was a negative trend in the incidence of hip fracture among both males (−0.023 per 100,000 per month, P=0.023) and females (−0.032 per 100,000 per month, P=0.019). No impact of COVID-19-related social distancing was noted.

Conclusions

In conclusion, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, vertebral fracture incidence considerably decreased with the implementation of social distancing measures.

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory pandemic caused by a new coronavirus known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. It began spreading rapidly in December 2019.[1] South Korea was once the second most affected country after China in early 2020, following a massive outbreak of COVID-19 that occurred in the Daegu region.[2] As of June 30, 2021, a total of 156,961 confirmed cases had been reported in South Korea. This pandemic has induced significant strain on the healthcare system.[3]

In February 2020, South Korea implemented social distancing measures to contain the spread of the disease and reduce the burden on healthcare resources.[4] Data on the incidence of osteoporotic fractures during COVID-19 are conflicting, with some studies showing that the incidence of fractures remained stable [5–8] while many others indicate a reduction.[7,9–12] Possible causes include mobility restrictions, changes in public behavior, and the allocation of medical resources and manpower.

Given the high heterogeneity in the behavior of osteoporotic fractures during COVID-19 so far, there is a need to study the local patterns and compare them to data from previous years. The incidence of hip fractures in South Korea is known to remain stable, but the incidence of vertebral fractures or fractures at other sites has not been studied thus far.[8]

The objective of this study is to describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of osteoporotic fractures in South Korea.

METHODS

1. Study subjects

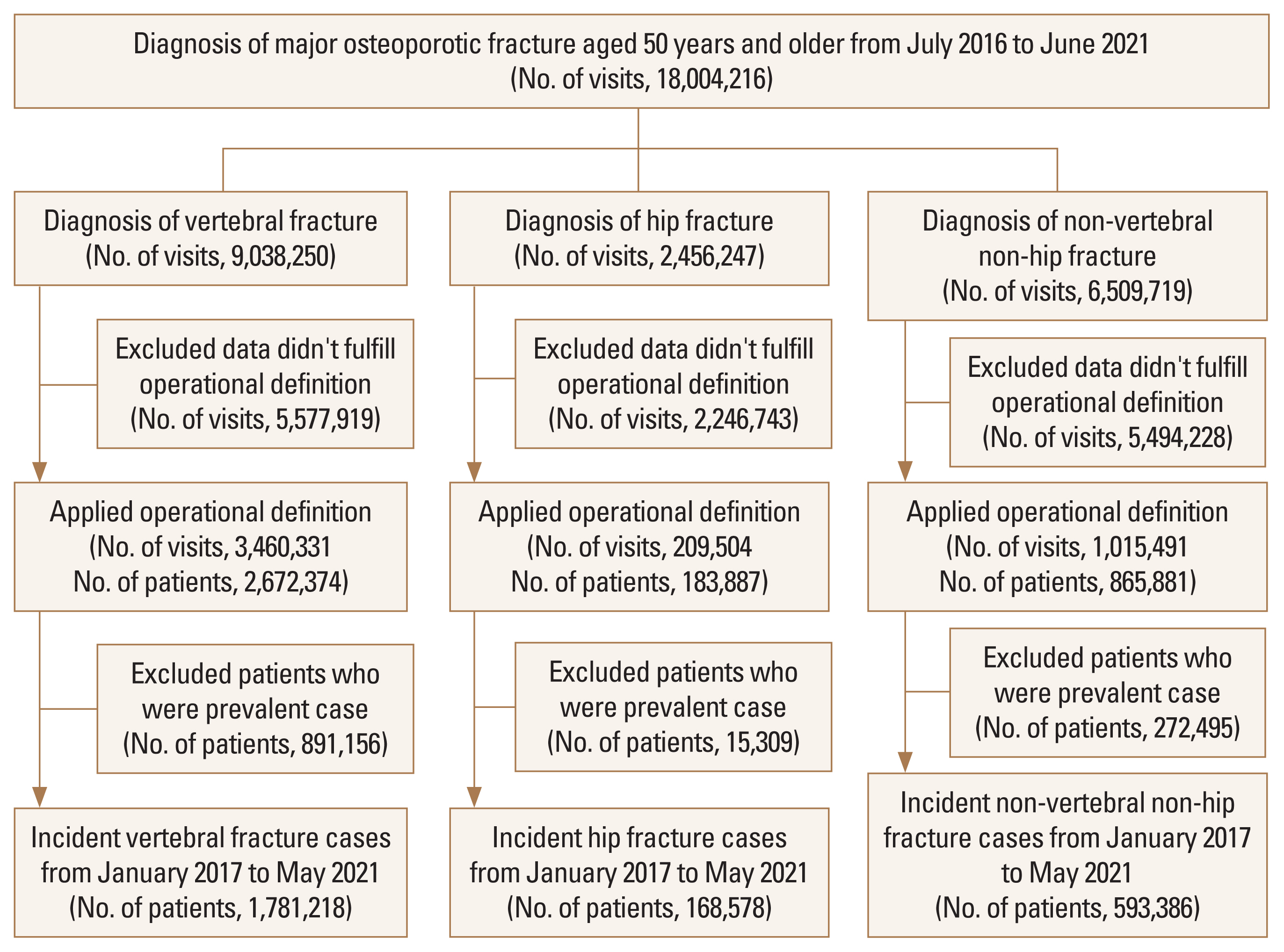

This retrospective nationwide study identified subjects from the Korean National Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) database from July 2016 to June 2021 (Fig. 1). We identified subjects aged 50 years and older at the time of osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporotic fracture events were defined using inpatient diagnoses with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth/Tenth revision codes and procedural codes based on previous studies.

2. Definition of osteoporotic fractures

The operational definitions of osteoporotic fractures of vertebra, hip, humerus, and distal radius were made using ICD-10 codes and procedure codes using the National Health Insurance Service data. ICD-10 codes for vertebral fracture were; S22.0 (fracture of the thoracic spine), S22.1 (multiple fractures of the thoracic spine), S32.0 (fracture of the lumbar spine), S32.7 (multiple fractures of the lumbar spine), T08.0 (fracture of the spine), M48.4 (fatigue fracture of vertebra), M48.5 (collapsed vertebra), M49.5 (collapsed vertebra), and M80.8 (other osteoporosis with pathological fracture). ICD codes of hip fractures were S72.0 (fracture of the femur neck) and S72.1 (trochanteric fracture). ICD-10 codes of humerus fractures were S42.2 (fracture of upper end of humerus), S42.3 (fractured shaft of humerus), and codes for distal radius fractures were S52.5 (fracture of lower end of radius) and S52.6 (fracture of lower end of both ulnar and radius).[13,14] Details about our operational definitions are provided in supplements (Supplementary Table 1).

3. Statistical analysis

We summarized the patients’ demographic characteristics (age group, and sex) and index year. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Monthly incidence rate (IR) of vertebral, hip, non-vertebral, non-hip (NVNH) fractures were presented as the number of newly diagnosed fractures in a month per 100,000 person-years from September 2016 to May 2021.[15]

Changes in levels and trends in the monthly IR of each fracture the before and after the COVID-lockdown (January 2020) were estimated using segmented regression models. The models were tested for autocorrelation using the Durbin-Watson statistics.[16] Since baseline IR differed between sex and age group, we assessed the changes in levels and trends in the monthly incidence for sex and age group separately. All P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS EG statistical software version 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

4. Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Korea) approved this study (2021–1866).

RESULTS

1. Clinical characteristics of study participants

From July 2016 to June 2021, there were 18,004,216 cases of osteoporotic fractures in patients aged 50 years and older (Fig. 1). Among these, 9,038,250 cases were diagnosed with vertebral fractures, and 1,781,218 incident patients were included from January 2017 to May 2021. Additionally, 2,456,247 cases were diagnosed with hip fractures, with 168,578 incident patients were included. 6,509,719 cases were diagnosed with NVNH fractures, and 593,386 incident patients were included, making vertebral fractures the most frequently reported osteoporotic fracture.

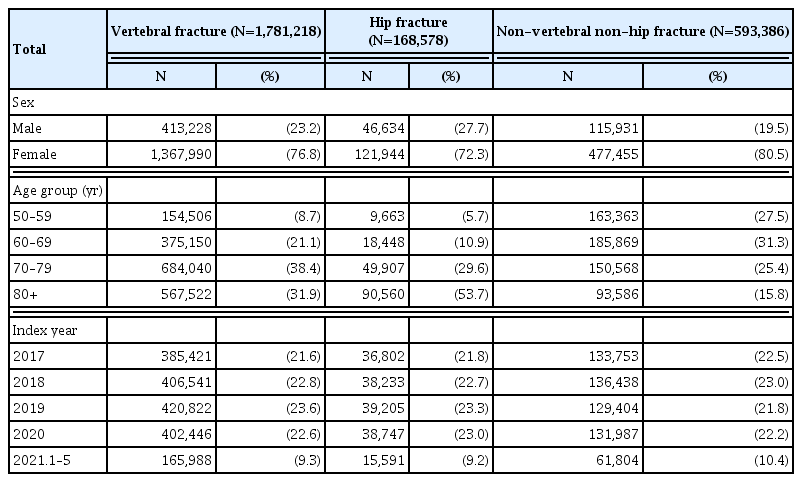

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of study subjects. Females were more common than males in all fracture groups (76.8% in vertebral fractures, 72.3% in hip fractures, 80.5% in NVNH fractures). Vertebral fractures were most prevalent in the 70 to 79 age group (38.4%), while hip fractures were most common in the 80+ age group (53.7%).

2. IR of osteoporotic fractures

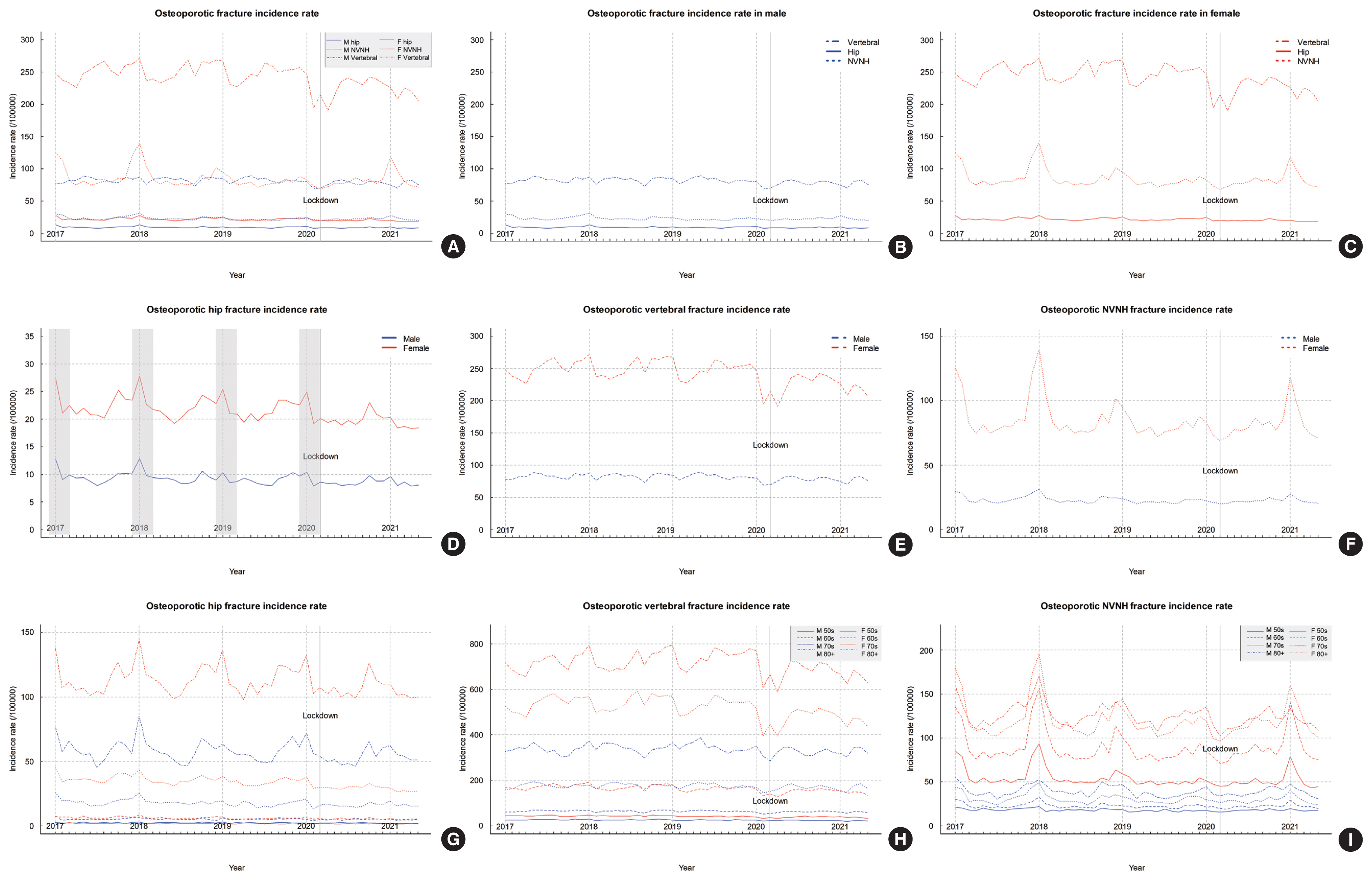

The IRs of osteoporotic fractures are presented in Figure 2. A notable decrease in vertebral fractures among females was observed during the social distancing period, while a mild dip was noted in vertebral fracture among males. The decline was greatest in the 70 to 79 age group and the 80+ age group.

(A) Incidence rates of osteoporotic fracture. Monthly incidence rates of osteoporotic fractures are shown according to sex (B, C), location of fracture (D–F), and age (G–I). M, male; F, female; NVNH, non-vertebral, non-hip.

There was a seasonality in hip fractures with a peak every winter. The peak decreased over time, showing a negative trend for both male and female. There was no difference in pattern within the social distancing period. A similar pattern was found for NVNH fractures with seasonality but no difference within the social distancing period.

3. Segmented regression analysis

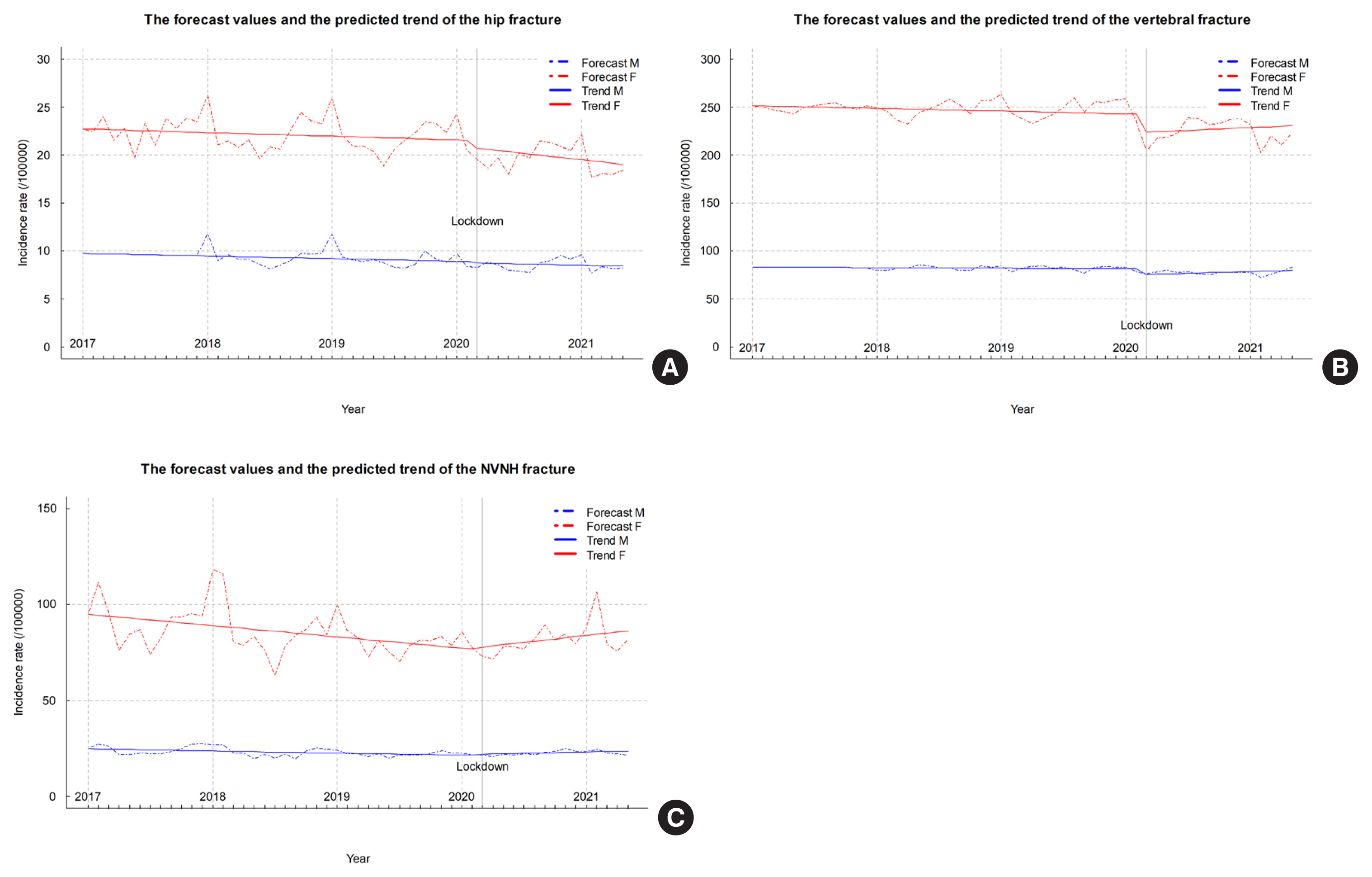

Segmented regression analysis with autoregression was done to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 social distancing period on osteoporotic fracture incidence (Fig. 3, Table 2). A step decrease was noted in vertebral fracture for both male (6.181 per 100,000, P=0.002) and female (19.299 per 100,000, P=0.006). There was no time trend in vertebral fractures. In subgroup analysis by age, the step decrease was statistically significant in the 70 to 79 age group and 80+ age group, but not in 50 to 59 age group and 60 to 69 group (Supplementary Table 2).

(A–C) Segmented regression analysis for monthly incidence rates of osteoporotic fractures. Analysis was done according to location of fracture. M, male; F, female; NVNH, non-vertebral, non-hip.

Parameter estimates, standard error and P-values from the full segmented regression models predicting monthly osteoporotic fracture incidence in South Korea from January 2017 to May 2021

There was a negative trend in hip fracture among both male (−0.023 per 100,000 per month, P=0.023) and female (−0.032 per 100,000 per month, P=0.019). No impact of COVID-19 social distancing period was noted. Negative trend was also found for NVNH fractures among both male (−0.095 per 100,000 per month, P<0.001) and female (−0.489 per 100,000 per month, P=0.004). Subgroup analysis by age revealed a step decrease of vertebral fractures among 70 to 79 females (−1.786 per 100,000, P=0.022). In nearly all fracture and age groups except for vertebral fractures among 70 to 79 females, there was a consistent negative trend and no impact of COVID-19 social distancing (Supplementary Table 3, 4).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found a step decrease in vertebral fractures during the COVID-19 social distancing period among adults in South Korea. Further, we observed a negative trend in hip fractures, which was not influenced by COVID-19 social distancing period.

The decline in vertebral fractures can be attributed to the limitation of mobility, since social distancing has led to a reduction of public movement and outdoor activities.[17] The decrease in vertebral fractures may also be partly attributed to a decrease in detection due to decreased healthcare use and imaging study. It is well known that the number of emergency department visits has decreased worldwide since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.[18,19] However, considering that the decrease in healthcare use is mainly non-orthopedic and that orthopedic admissions display a relatively minor change, it is reasonable to infer that mobility restrictions have contributed to the reduction in vertebral fractures.[20]

It is interesting to note that the incidence of hip fractures did not decrease within the COVID-19 social distancing period, in contrast to the incidence of vertebral fractures. Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies reporting that the incidence of hip fractures and low-energy trauma did not decrease during the COVID-19 pandemic.[21–23] The reason for the difference in these patterns is not fully understood.

Age-adjusted hip fracture rates worldwide show differences in the trends and their timing between countries and continents, with some countries showing a plateau or beginning to decline in hip fractures rates, while others continue to increase.[21,24] In South Korea, the incidence of hip fracture is known to increase rapidly until 2012 from a nationwide database.[25] However, our study found that there is a negative trend in hip fracture incidence, suggesting that the decline may have begun, as in other countries such as the USA or Taiwan.[26,27] The etiologies of the secular patterns are not fully understood and declared factors include urbanization, birth cohort effects, changes in bone mineral density and body mass index, osteoporosis medication use, and/or lifestyle interventions, such as smoking cessation, improvement in nutritional status, and fall prevention.[24] Further studies are needed to confirm the change in the secular trend and to clarify the etiology.

Our study has several limitations. First, the data we collected did not include a lifetime history of previous fractures and a diagnosis of osteoporosis. Considering baseline fracture risk based on these histories would be useful for analyzing the true fracture trend and IR in future studies. Second, this study was a retrospective observational study using a national health insurance claims database, and there was a possibility of misclassification in defining study subjects. However, we made efforts to adopt a valid operational definition, incorporating diagnostic codes, procedure codes, and hospital admissions. A recent study comparing diagnoses from claims databases with medical records showed overall positive predictive value rates ranging from 59.7% to 98.2% for osteoporotic fractures at various sites.[28–30] Thus, we believe that misclassification of study outcomes might be low and would not significantly affect the main results. Third, due to the nature of this study using a national health insurance claims database, only clinical fractures were detected, and morphometric fractures were not included. Fourth, the incidence of osteoporotic fractures described in this study might be overestimated due to subsequent fracture within the same year, as we summed up monthly incidences of osteoporotic fractures rather than calculating yearly incidence. It is important to note that the objective of this study is to determine the trend and impact of COVID-19, not to provide epidemiological data, and should be interpreted accordingly. Lastly, our data were limited to June 2021, and we were unable to describe the trend after COVID-19. Further studies are needed to determine whether the changes found in this study will return to their original state after COVID-19.

In conclusion, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, vertebral fracture incidence considerably decreased with the implementation of government social distancing measures.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Health Insurance Review & Assessment (HIRA) Service of Korea for sharing invaluable national health insurance claims data in a prompt manner for this study (Project number: M20220103754).

Notes

Funding

This study was supported by research funding from Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research (Namki Hong, 2018).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board of Asan Medical Center (Seoul, South Korea) approved this study (2021-1866) and was conducted consistent with the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.