INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined osteoporosis as a metabolic bone disease in low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue result in bone fragility and a consequently an increased risk of fractures. Osteoporotic fractures are caused by mechanical forces that normally do not result in fractures, known as low-energy trauma.[

1]

In worldwide, hip fracture is one of the leading causes of severe morbidity and disability in elderly patients, and it increases the economic burden on the health care system.[

2-

5] The incidence of osteoporotic hip fractures increased between 2005 and 2008.[

6] The costs and social burdens of osteoporotic hip fractures are increasing rapidly in national health care systems, and as a result, intense efforts are being made to prevent second osteoporotic fractures in people who have already had their first hip fracture.[

1,

2,

6]

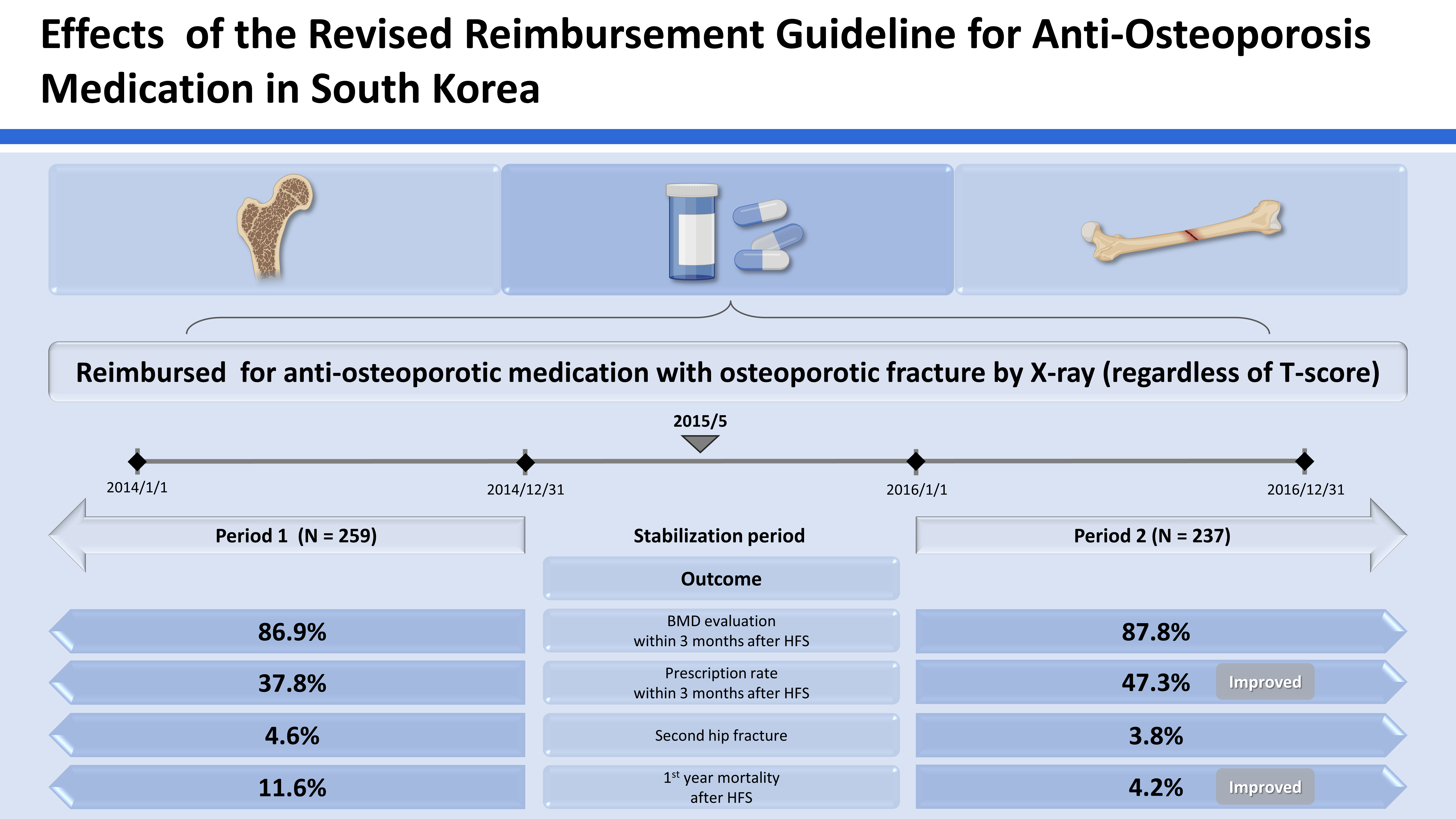

Recently, the Korean National Health Insurance (NHI) reimbursement guideline has been revised according to the government policy with the aim of preventing secondary osteoporotic fractures in Korea. Through the revision, the anti-osteoporotic drug could be reimbursed for 3 years, regardless of the level of the T-score, if an osteoporotic fracture was diagnosed by X-ray, since May 2015.

The revision of reimbursement guideline could affect physicians’ practice in the real world.[

7-

9] However, there has been few studies that evaluated the effects of the change in insurance guideline.[

10] Thus, our purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of the revision of the reimbursement guideline. We compared (1) the rate of bone mineral density (BMD) measurement within 3 months after hip fracture surgery (HFS); (2) the prescription rate of antiosteoporosis medication within 3 months after HFS; (3) the incidence of secondary fracture; and (4) the first-year mortality after HFS in a single institution.

METHODS

1. Patients

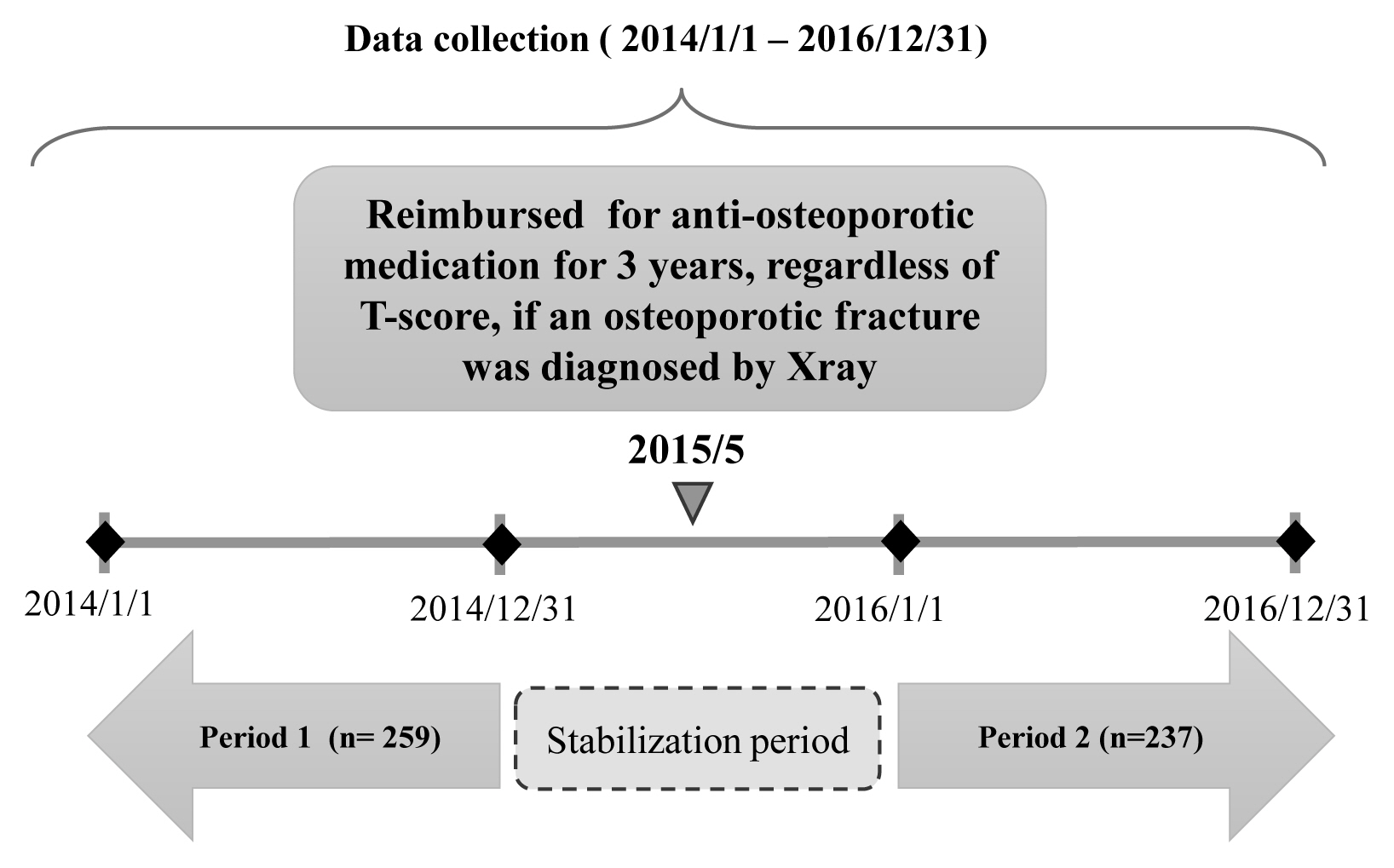

We conducted a before-after study with the revision of the reimbursement system as a reference period. The medical records of 515 patients who underwent HFS at a single tertiary referral hospital from January 2014 to December 2016 were reviewed. As the reimbursement system was revised in May 2015, 2015 was set as a 1-year window period. Therefore, the patients who were operated in 2015 were excluded. In addition, 1 patient diagnosed with a pathologic fracture, 1 patient with a periprosthetic fracture, 3 patients with high energy trauma, and 14 patients younger than 50 years of age of which the cause of fractures was unrelated to osteoporosis were further excluded (

Fig. 1).

We defined the group from January 2014 to December 2014 as period 1 and the period from January 2016 to December 2016 as period 2. Patients were classified into period 1 group and period 2 group accordingly (

Fig. 2). Finally, the records of 496 patients were included in the analysis - 259 patients in period 1 group and 237 patients in period 2 group.

2. Hip Fracture Surgery

The type of HFS, internal fixation versus hip arthroplasty was decided according to the fracture type, patient’s age, activity level before the injury, and underlying comorbidities. All internal fixation using cannulated screws, dynamic hip screws, Intramedullary nails and hip arthroplasty including total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty were performed with the standard technique. Surgeries were usually performed within 1 day to 3 days after preoperative evaluations and medical preparations.

After internal fixation, a tolerable range of motion of the hip was immediately permitted, and wheelchair ambulation was started at 2 or 3 days postoperatively. Patients walked with protected weight-bearing and used assistive devices (wheelchair, walker, crutches, or cane) 3 to 10 days after the operation. As their walking ability improved, their assistive devices were changed appropriately by a physical therapist. To prevent thromboembolism, intermittent pneumatic compression devices with thigh-length anti-embolic stockings were applied and an ankle pump was encouraged in bed during the hospitalization. After discharge, patients were routinely followed up at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months postoperatively and annually thereafter.

We also evaluated gender, age, medical comorbidities (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue disorder, peptic ulcer disease, mild liver disease, moderate or severe liver disease, diabetes mellitus, hemiplegia, and renal disease) as potential associated factors.

Anti-osteoporosis drugs in this study included any kind of bisphosphonates (alendronate, etidronate, pamidronate, risedronate, and zoledronate), selective estrogen receptor modulators (raloxifene, raloxifene/cholecalciferol, and bazedoxifene), and teriparatide.

When T-score was −2.5 or less, the patients was defined as osteoporosis according to WHO osteoporosis criteria.[

11-

13]

3. Statistical analysis

Student’s t-tests or Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous data, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical data. For all other tests, a 2-sided P value of 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of our hospital (IRB no. B-1610-366-103). The need for informed consent from the study population was waived by the board.

RESULTS

The 259 patients were operated in period 1 and 237 patients in period 2. Basic demographics were similar between 2 groups, except for the type of surgery. Compared to period 1 internal fixation for hip fracture was more frequently performed in period 2 (

Table 1).

The period 2 group showed a higher prescription rate of anti-osteoporosis drugs within 3 months, although there was no significant difference in rates of BMD examination between both period groups. However, the incidence of second hip fracture did not differ between both periods. First-year mortality in period 1 group was higher than in period 2 (

Table 2).

In terms of BMD T-score, 72 patients in period 1 and 62 in period 2, who had T-score higher than −2.5, could not be prescribed anti-osteoporosis drugs if the insurance guideline were not revised. Among these patients, 51.6% (32/62) were treated in period 2, while 33.3% (24/72) were treated in period 1 according to the revised insurance guideline (

Table 3).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the effects of the revised NHI reimbursement guideline for anti-osteoporotic medication in 2015. The revised reimbursement guideline allowed the anti-osteoporotic medication in patients with osteoporotic fracture even when the T-score was higher than −2.5. After the revision of reimbursement guideline, the prescription rate of anti-osteoporosis drugs significantly increased. Moreover, the 1-year mortality decreased significantly after the revision, although the BMD measurement and the incidence of the secondary hip fracture remained unchanged.

Some studies showed that changes in reimbursement guidelines for diagnostic tests or treatment for osteoporosis affected practical behaviors in osteoporosis treatment.[

7-

9] In 2007, Australia’s Medicare initiated reimbursement for dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) tests for elderly patients aged 70 or older to delay or prevent the occurrence of fractures. When comparing before and after the introduction of the DXA reimbursement guideline, the proportion of DXA referrals significantly increased in both men and women.[

7] However, Stuart et al. [

8] found that the changes in reimbursement guidelines had little impact on the reduction of fracture incidence in the elderly, and fracture rates increased in 2012 compared to 2006. The province of Ontario in Canada changed its reimbursement policy for DXA tests in 2008. The intent of revised reimbursement policy was to reduce DXA rate in low-risk group and preserve DXA for the high-risk groups. The changed policy succeeded in reducing DXA usage in low-risk groups and increasing it for high-risk men but not in women.[

9] In current study, the prescription rate of osteoporosis medication increased from 38% to 47% after the revision of reimbursement system. As seen in previous studies, the change of reimbursement policy plays a major role in changing the utilization of diagnostic tools and prescription rate, but not necessarily in the fracture rate. In our study, the secondary fracture rate did not differ between 2 groups, similar to the previous studies.

Historically, the NHI reimbursement guideline has been revised according to the government policy on osteoporosis management. In 2011, the guideline was revised to expand the diagnostic criteria of osteoporosis from a T-score of −3.0 to −2.5 and to increase the reimbursement period from 6 months to 1 year after diagnosis. Koo et al. [

10] evaluated the effects of revisions in policy in 2011 and 2015 for anti-osteoporotic drugs in Korean women aged 50 or older using the NHI registry. They showed that the prescription rate of anti-osteoporotic medication significantly increased after the second revision of reimbursement guideline. However, the rate of secondary hip fractures and mortality were not analyzed, and the T-score and the proportion of the subjects who could be reimbursed after the revision of the guideline were unavailable as it was a registry study. In contrast, we were able to follow-up on the patients after the inclusion period and report the rate of secondary hip fracture and mortality after the index HFS. Our study yields a unique outcome where the first-year mortality after HFS decreased prominently from 11.6% to 4.2% after the change of policy.

Osteoporotic hip fractures are an important cause of mortality in the elderly.[

14-

16] First-year mortality after hip fracture was 5 times greater in males and 3 times higher in females.[

14] Some studies found that zoledronic acid improved the mortality of patients with hip fractures.[

17-

19] Similarly, our study found that after the revision of the policy prescription rate of anti-osteoporosis medication increased and the first-year mortality rate in osteoporotic hip fracture patients decreased. As in the previous study, it is thought that the increase in the prescription rate of osteoporotic medication lowered mortality.

Our study has several limitations. First, we only included hip fractures among osteoporotic fractures. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) guidelines, osteoporotic fractures included vertebral, hip, and distal radius fractures.[

1] When other osteoporotic fractures are included, the outcome might be different. However, hip fractures are the most severe type of osteoporotic fracture and is most closely related to severe morbidity and mortality even after surgical treatment. Second, this was a single-center study. For generalization, a multi-center study with a larger number of patients would be needed in the future. Third, there might be some confounding factors, such as the advancement of surgical techniques or type of osteoporotic medications that might affect the outcome of this before-after study. However, the surgery was performed by the same staff during the entire study period and the rehabilitation protocols remained the same.

The revision of insurance guideline in May 2015, which increased the prescription for osteoporotic fracture patients and extended the coverage period for anti-osteoporotic drug therapy, was associated with the increase of the prescription rate of anti-osteoporosis medication and decrease of first-year mortality rate in osteoporotic hip fracture patients.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print